This is a talk I gave at Sunrise in Sydney, Australia in April 2025. Slides and full text below.

Let’s go back in time, to the birth of the internet.

I know, I know, a lot of you nerds are thinking “amateur – I was dialling up a BBS when you were still in nappies”. But this was how most people encountered the internet for the first time as it started to become mainstream.

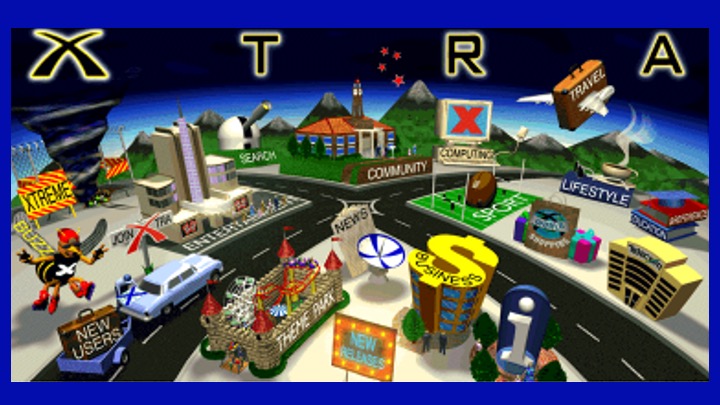

Your “front door” to the internet in those early days probably varied:

A university homepage

Yahoo!’s front page

Or, if you were lucky enough to be in Aotearoa at a certain point in time, the Xtra front page

All of these starting points had something in common: a top-down taxonomy. Where do you want to start your journey on the information superhighway? News? Business? Entertainment? A galaxy of possibilities that, well, sounded a lot like sections in a newspaper or areas of the library.

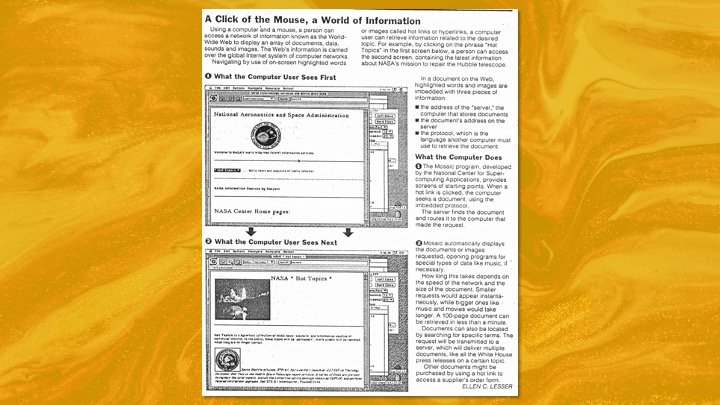

Here’s what the New York Times wrote in 1993:

Click the mouse: there’s a NASA weather movie. A few more clicks, a speech by President Clinton… music recordings compiled by MTV…

… a small digital snapshot reveals whether a coffee pot at Cambridge University is empty or full.

It’s a quaint vision now. Utopian. Pastoral. Idyllic.

Like reading about some little country town.

When we live here now.

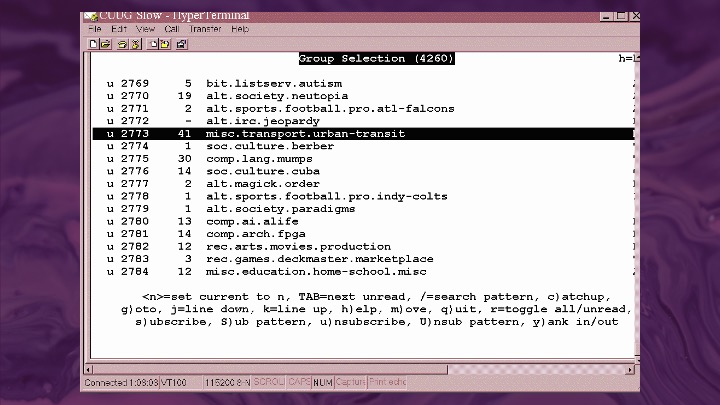

The social heart of that little village was originally Usenet. For the Gen Z in the audience, you can think of Usenet as a kind of proto-Reddit – a bastard lovechild of email and a bulletin board.

In those communities, you could find people from all over the world interested in the same things you were: science, technology, books, TV shows, hobbies.

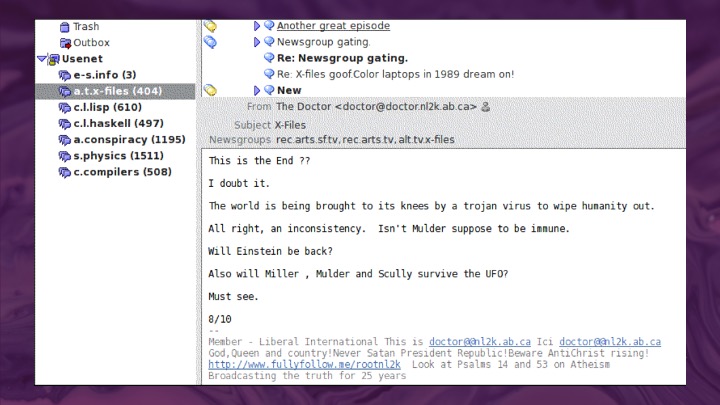

This became my first home on the internet – in The X-Files fandom.

This was my first experience with Transformative Fandom – a community that didn’t just consume media but debated it, reimagined it, and created art and stories expanding its universe.

Looking back, so much of what we take for granted online started in these early communities. This is where online culture was born

Initially, most online etiquette was dictated by form. Posts needed to be concise. Long email signatures were annoying. Posting large files where they would clog up news readers was downright rude.

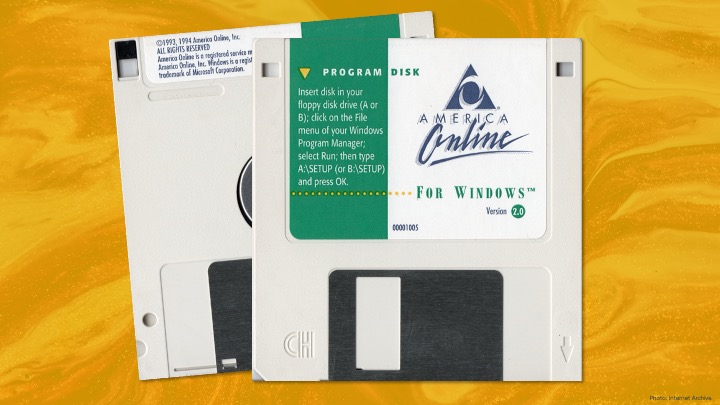

Before 1993, the internet belonged to the relatively tech-savvy, often university students and researchers.

But Usenet culture changed forever in September 1993, when AOL gave its massive user base access. The influx of new users overwhelmed the community’s ability to teach them the ropes. “Eternal September,” marked a permanent shift in online interaction.

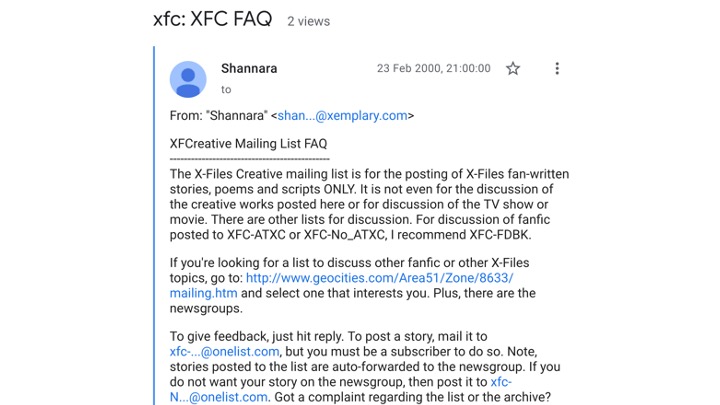

Usenet communities had to find ways to make the experience work for everyone.

They would post lists of Frequently Asked Questions – that’s where it comes from – hosted on personal websites, which became cheat sheets for new members trying not to look clueless.

This phase of the pre-web internet was defined by being:

User-created – we made everything ourselves

Self-governing – communities came up with their own rules, norms, expectations

Community-driven – it was focussed around bringing people together in neighbourhoods

Decentralized – there were no corporate landlords

Was it utopian? No. It was small, homogeneous, and hard to navigate.

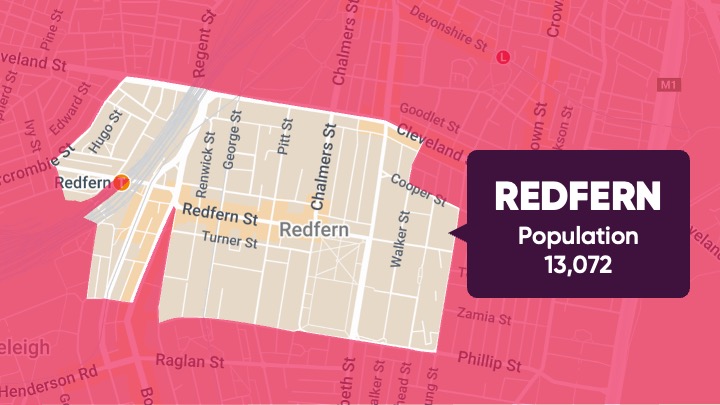

In 1994, there were only about 10,000 websites and 2,500 web servers. That’s fewer than there are people that live in Redfern.

You could buy physical directories – actual books – that mapped the “information superhighway” because it still made sense to have an offline map of the online world.

Search engines were years away from making things findable. We relied on hand-curated directories maintained by individuals.

Jean Armour Polly, the librarian who first coined the phrase “surfing the internet,” liked the metaphor because finding your way wasn’t easy – like the sport it required skill, patience, and a sense of adventure.

I was a baby lawyer in the 1990s, taking my career very seriously. So you can imagine how twitchy it made me when every X-Files story I read started with a lengthy disclaimer begging not to be sued

Turns out it wasn’t just culturally transgressive to read stories where Mulder was doing more than just throwing Alex Krycek against a wall – it was potentially legally transgressive too.

Much of this anxiety stemmed from Anne Rice.

Her books had always been popular but her Interview with the Vampire gained new prominence with the 1994 film adaptation starring Tom Cruise.

Rice was clear about her disapproval of fan fiction. In a 1995 chat, she said: “I’m very possessive of my characters.

I think it would hurt me terribly to read anything with some of my characters. I hope you’ll be inspired to write your own stories.”

By 2000, she was sending cease-and-desist letters to fans – a move later copied by 20th Century Fox for The Simpsons and The X-Files, and by Warner Brothers for sexually-explicit Harry Potter fanfiction.

Fans usually folded, lacking resources to fight legal threats. Today, of course, we’re very familiar with corporations wielding content takedown notices and cease and desist letters, but back in the late nineties, this seemed a lot more confrontational and frightening.This clash represented a new tension between commercial content producers who wanted to leverage the internet to engage fans, but didn’t want those fans doing whatever they wanted online.

Writing in HotWired in 1997, Steve Silberman summarized the “War on Fandom”:

“The problem is that the nature of fandom has changed fundamentally in the past 30 years, while perception of the role of fan culture in marketing campaigns has not. Both the fans and the media companies want to cheat a little.

The media companies want to parade their Web savvy in the marketplace and funnel all Net traffic into a few commercial sites.

The fans want freedom of speech and assembly in sites of their own choosing.”

So, the first thing you need to know about fans is that we will do what we like with your characters.

The second thing? We’re horny.

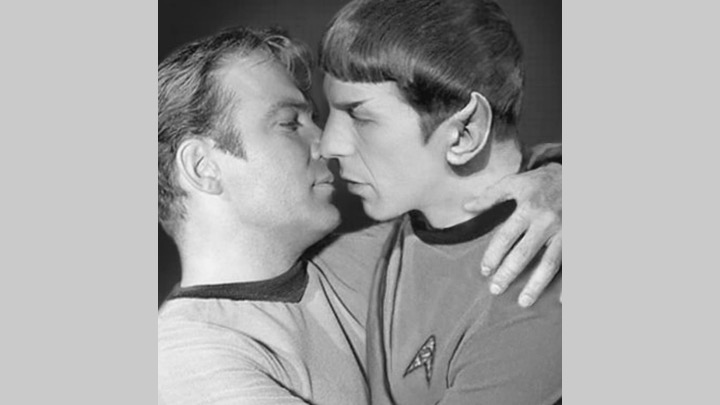

Actually, this is probably the one thing you already know – because fandom gets reduced to the cliché of weirdos writing explicit stories about Kirk and Spock in the 70s.

But transformative fandom has a long, proud history of exploring relationships between characters never paired on screen.

Valkyrie and Captain Marvel

Draco Malfoy and Harry Potter

Betty and Veronica

And those old men in the Conclave

And what are two things advertisers hate? Infringing IP and explicit content.

From the beginning, fandom didn’t fit with the idea of a corporate-owned internet. We built our own spaces:

Fan-run archives – where we could host our art and stories

Our own forums – where we could discuss shows and films and books

Our own websites

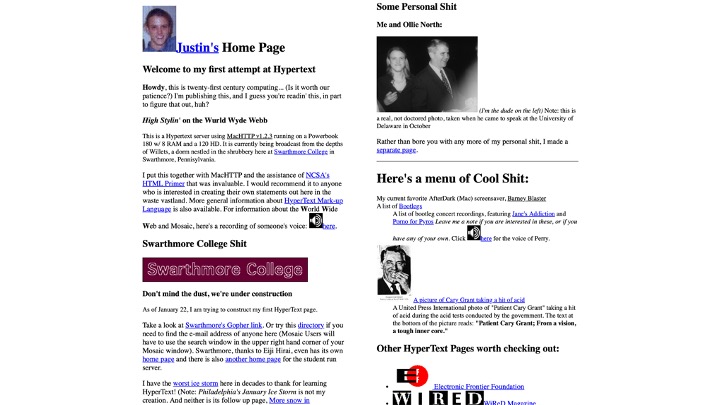

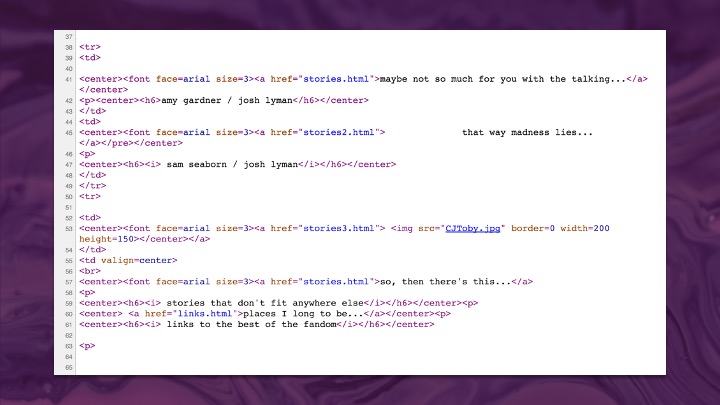

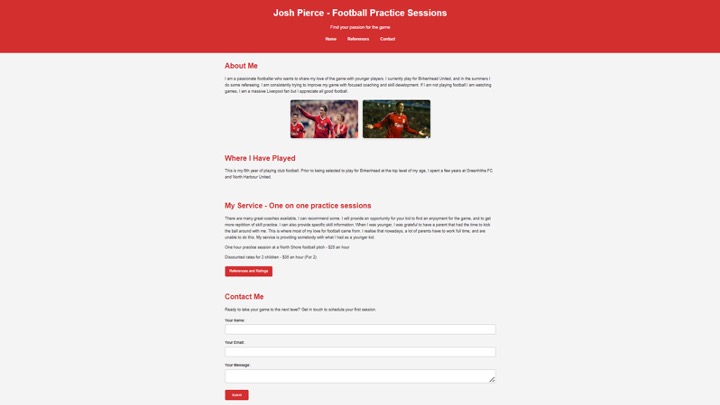

This is mine – the first website I ever built.

Some things about it:

I built it because I was worried about my stuff disappearing

My friends taught me, I didn’t go to a coding camp or have a book of HTML.

I did a lot of “view source” back when this was still useful.

I built it because I wanted control of my own stuff.

These motivations were fundamental in fan communities:

Seeking permanence

DIY approach

Peer-to-peer learning

Control over our content

So, In the early 2000s, the Usenet/mailing list era evolved into Web 2.0.

As fans, we shifted from Yahoo Groups and we landed on LiveJournal …

… and Tumblr – both darlings of web 2.0. While the buzzwords were all about user-generated content, open data, and interoperability

The demon of capitalism was bearing down on us all.

David Karp, Tumblr’s founder, criticised YouTube: “They take your creative works – your film that you poured hours and hours of energy into – and they put ads on top of it.

They make it as gross an experience to watch your film as possible.

I’m sure it will contribute to Google’s bottom line; I’m not sure it will inspire any creators.”

Look where we are now.

As venture capital and advertising became the drivers, fans were often thrown under the bus (along with marginalized groups, activists, and survivors). It takes time and resources for a platform to determine whether something flagged as “offensive” should actually be removed.

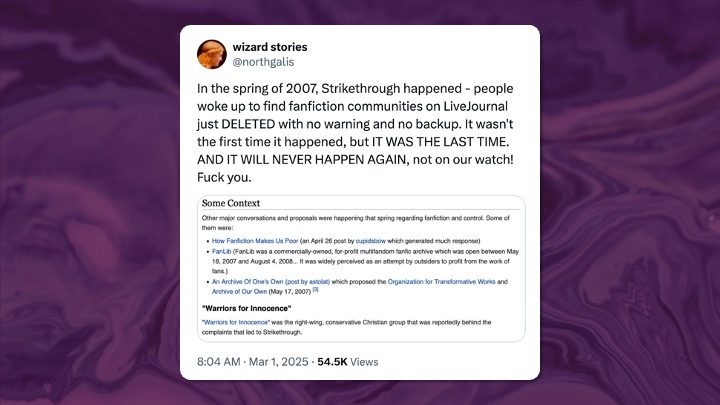

For LiveJournal, this came to a head in 2007 with “Strikethrough” – a mass banning of hundreds of fan journals on the grounds of explicit content

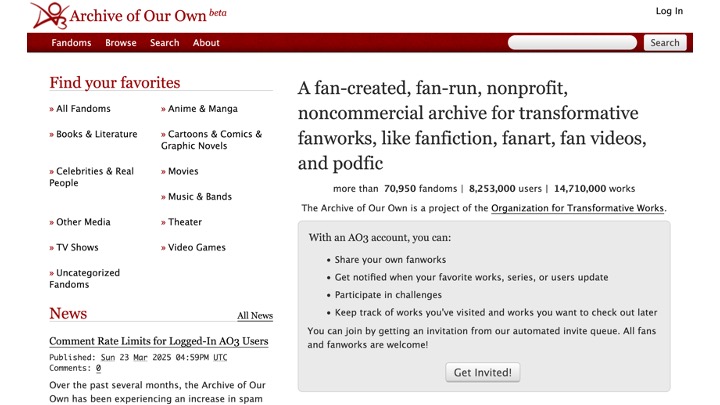

And which led directly to fans building An Archive of Our Own. Fans realised that the transgressive nature of transformative fandom was always going to be at odds with companies that wanted to make money off advertising, or were unwilling to defend content on their platforms from complaints and threats.

AO3 is a noncommercial and nonprofit central hosting site for transformative fanworks such as fanfiction, fanart, fan videos and podfic built and run entirely by fandom volunteers – hosting 14.6 million uploaded fanworks, 8.1 million registered users, and has fanworks in over 70,000 fandoms.

Fans have always been acutely aware of impermanence – something the rest of the world is just starting to recognize might be a problem.

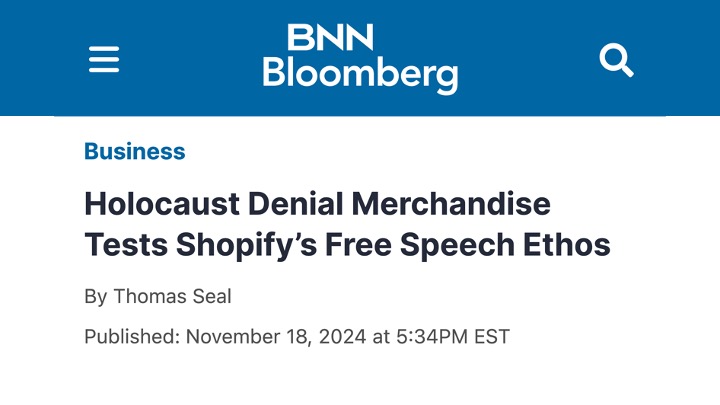

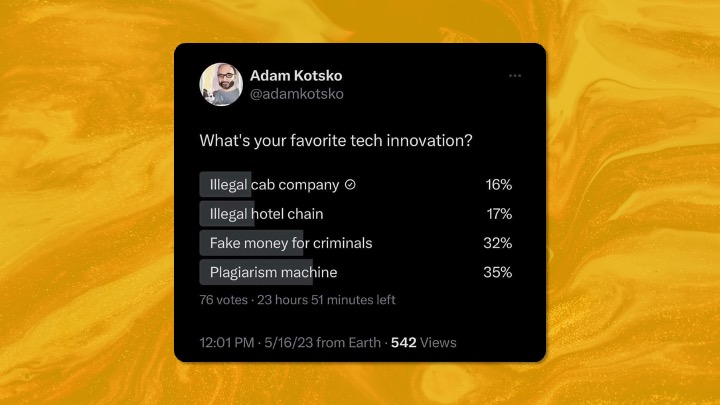

Fans have long been canaries in the coal mines. Corporate landlords don’t want your infringing IP or explicit content, but they might tolerate Nazis if they pay their bills.

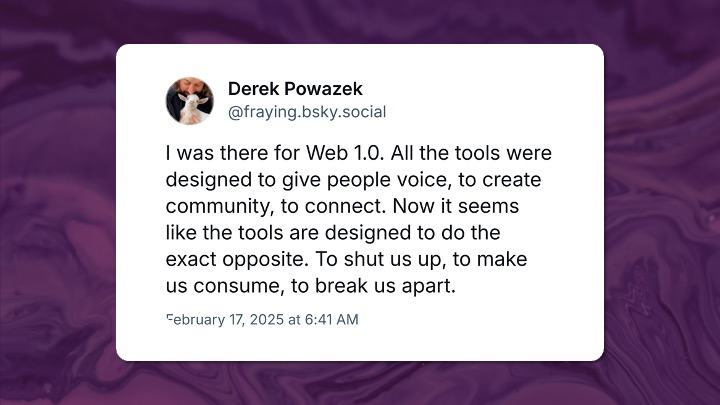

We now exist in walled gardens, monitored by surveillance capitalism, and incentivized to perform engagement through rage.

Nobody wants another “the internet is bad” talk. We all know the utopian vision didn’t materialize.

But, as Molly White recently wrote, the good internet is still there, just outside the walls:

“The walled enclosures that crowded out much of that acre of developed land still reside within an infinite expanse of possibility.

There are no limits to the web – if it has borders, they are ever expanding.

We may feel as though we are trapped in a tiny, crowded, noisy space, but it is only because we don’t see over the walls.”

This inspired me last year to build my second-ever website – a single-serve site to help plan a new layout for my LEGO city.

This is my city. It’s a covid problem that got out of hand don’t talk to me.

This site became a finalist in the Tiny Awards, which:

“exist to celebrate the personal internet, the other web, the one that is small and handmade and isn’t trying to sell you anything or monetize anything but which instead is about people using the digital tools we all have access to to make the sorts of small, personal experiences that you tend not to see ‘in feed’.”

This is what I want to focus on this year: This other web. The good internet.

Having built only two websites, twenty years apart, gave me insight into how much has changed, for better and worse.

In some ways, we’ve made it easier. Everything is templated. Squarespace lets you throw up a slick site in minutes.

But somehow they all look the same.

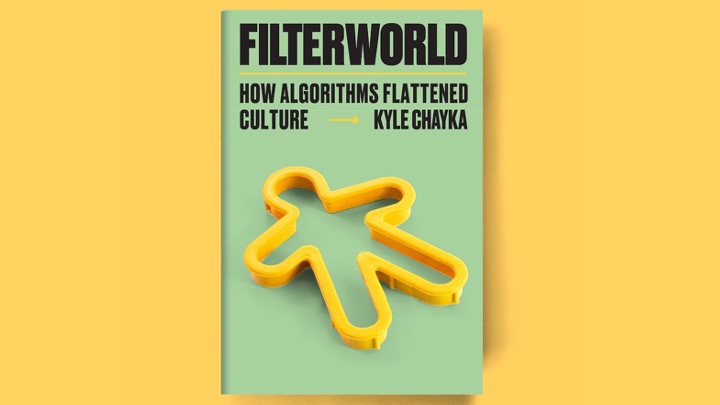

What Kyle Chayka calls “Filterworld” – where algorithms drive all our tastes toward the same flattening end, making coffee shops, Airbnbs, and interior design soulless and drab.

Building for the web is easy, and we’ve forgotten how.

And if you know how, when was the last time you showed someone in your life how to make a website?

I did it last weekend. My nephew Josh is a really good football player who wants to start coaching kids. So he needs a website and he asked me what service he should sign up for and all I could think was

Why not make it himself?

I knew his eyes would glaze over if I started explaining html from scratch. And so he asked an LLM for the basic code for a football coaching website and I showed him how to save it to his machine. You would not believe how he gaped when he clicked on the index file…

… and how his mind was blown when we added basic CSS. Within 20 minutes he was debugging mistakes the AI was making (and boy does it make mistakes) and changing the code himself.

And within an hour he had a site that started to feel like him.

Here’s what’s easy:

- Writing basic HTML (with AI help available)

- Getting a domain name (relatively inexpensive)

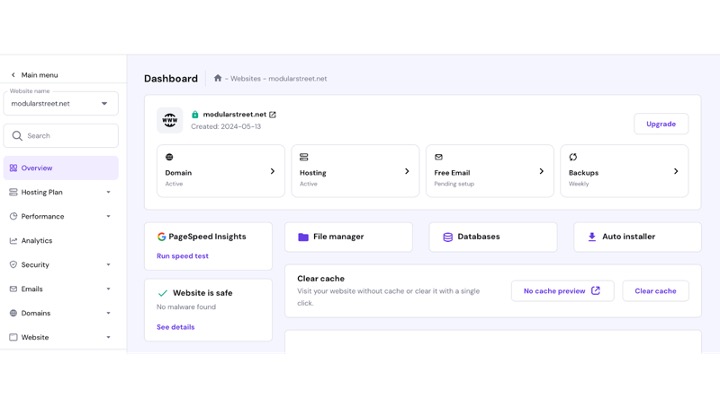

But weirdly hosting remains a challenge. In the olden days, you got free webhosting from your ISP. Now, storage costs are trivial, yet finding an easy-to-use, reliable webhost is difficult.

And when you find one, you’re confronted with FTP clients and technical jargon. I had to dredge my brain to remember how to use this.

The principle here is something I learned from Grey’s Anatomy…

…which is a surgical teaching principle of “see one, do one, teach one.”

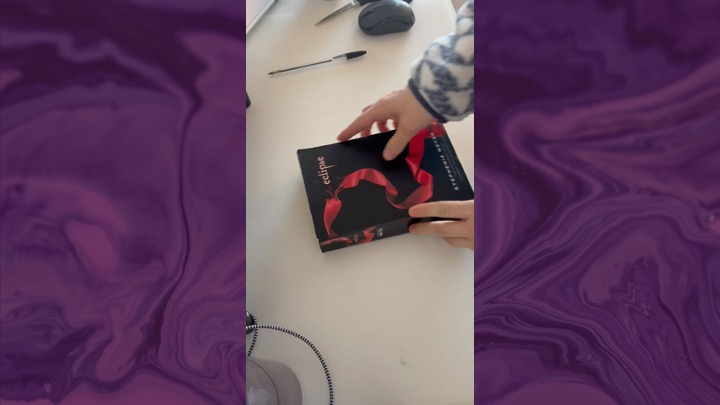

Fandom has always thrived on peer-to-peer teaching – like fan-binding, teaching others to make physical books of digital fiction and to rebind favourite books series. I learned to do this over the summer from watching fan tutorials on tiktok.

What if we applied see one, do one, teach one to building for the web again.

We’ve stopped exercising our digital agency. Manual processes feel too hard (sorry, Fediverse fans).

Here’s what we need to change:

WHERE we consume

HOW we consume

WHAT we consume

Let’s start with how…It’s long past time to turn your back on “recommended,” “for you,” and “you might like” – and to control your scroll.

Until recently, this was nearly impossible with social media. Being on Twitter, TikTok, or Instagram meant being at the mercy of whatever black-box algorithm drove the most engagement – a firehose to the face. These platforms quickly learned that hatred, conflict, and fear drive engagement.

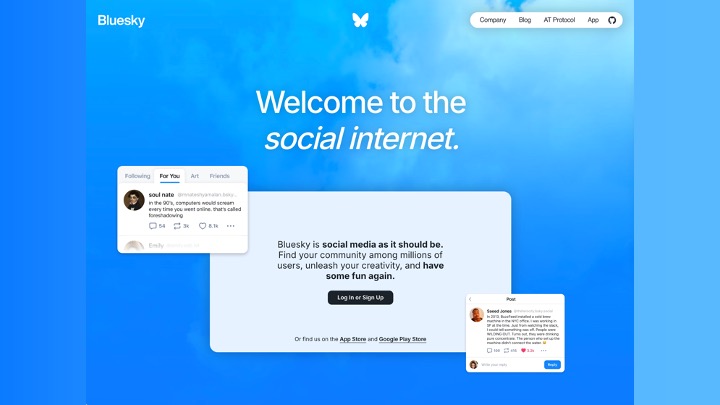

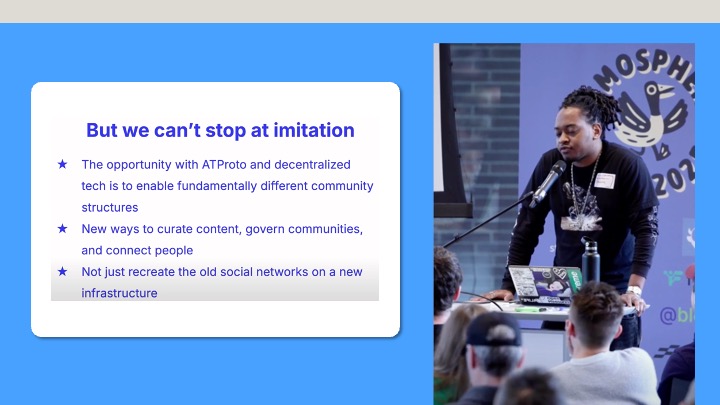

Like many, I joined Bluesky when Twitter was acquired. I thought it was nostalgic but not revolutionary. I told people, “Whatever comes next won’t be a Twitter clone.” Now I’m not so sure.

You might have seen Bluesky CEO Jay Graber at Sx recently wearing her “World without Caesars” shirt, to contrast with Meta CEO’s Zuck or Nothing. Bluesky doesn’t want emperors or to control your feed.

Old Twitter let you create “lists” to check in on specific accounts. But Bluesky lets you make entire feeds, customizing your whole social media experience. Mute words, block accounts, filter out Amazon links, hide NSFW content, or highlight mentions of your favorite blorbo – all possible with custom feeds.

I’ve been spending time with the team building Graze – a low/no-code feed builder for Bluesky that’s changed my whole experience. Make feeds public or private, opt in or out, use them for community building.

Similarly, Rudy Fraser and BlackSky continue doing amazing work with feeds by and for Black users.

Speaking at a conference recently Rudy described Bluesky as a skeuomorphism. It looks and feels like twitter but we need to move beyond that shorthand to take advantage of everything the new infrastructure offers us.

I don’t know if Bluesky’s growth will last, but the ability to curate your own social media is something I’ve wanted for years

I’m also interested in apps like Tapestry, which bring all your various feeds into a central place. I’m not sure I want to scroll my hockey tumblr thirst posts alongside US political doom, but I am interested in what’s next.

How we live online needs to change.

Next up is WHAT we consume.

Clive Thompson wrote a great piece on “Rewilding your Attention” – thinking about how we can go strolling to look for weird things online.

I want everyone here to take up the banner of reweirding the web.

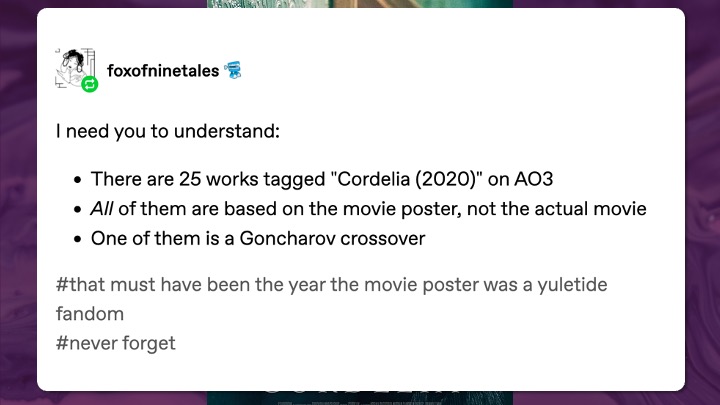

Fans love weird – we’ve invented a whole fandom around a fake mob movie from the 70s that came about because someone posted a picture of their shoe. It referenced a Scorcese film called Goncharov that didn’t exist. Someone on tumblr tagged it “this idiot hasn’t seen Goncharov” and away we went.

People posting essays about the themes of the film, the characters, how certain scenes should be interpreted, creating the posters, making the soundtrack.

There are over 700 Goncharov fanfics on AO3. Scorcese’s daughter texted him to ask if he’d seen it.

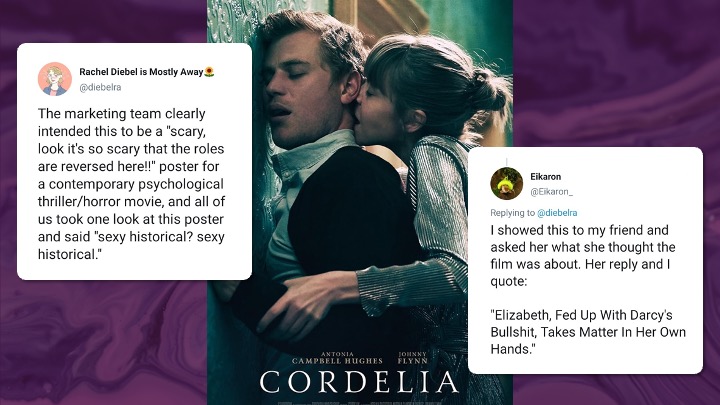

We’ve misread posters and turned THAT into fandoms. When the poster for this film Cordelia dropped, everyone on tumblr somehow saw this as a period film. You have to stare at it to realise it’s not – they’re wearing contemporary clothes.

Anyway – one of them is a Goncharov crossover.

My point is we need to take that weirdness everywhere.

Here’s a bunch of things I’ve seen just in the last month or so:

Global capslock was a project where you ran a little client in the background and, when one person pressed capslock it came on for everyone else:

This site shows you where the closest panda is and what its name is.

Here are your closest pandas!

My friend Erika started painting chickens to deal with the state of things in America. Then she decided to try and reset the timeline to before the internet took the particular turn that created Facebook. What if we did the same simple interaction, but *not* in order to compare the hotness of nonconsenting teens? Clickens was born.

Traffic cam photo booth. Find your nearest traffic cam, go and pose for a pic.

And then this one is hard to describe:

I tried it out, 30 seconds to record is harder than you think!

Imagine if everyone in this room made something fun, weird, pointless, useful. Something that solved a problem only you had. Or didn’t solve anything at all but made you smile. Or made your nephew smile.

Finally, WHERE we consume – We need to think differently about our digital neighbourhoods.

Everything old is new again – like the return of Digg.

But we also need genuinely new things. We didn’t know we needed Twitter when we built it. Remember when everyone mocked it as the app where you posted your sandwich – not dismantled democracy?

We need to stop thinking about audience; and start thinking about discovery in an era when AI-generated content has destroyed search.

I too have a newsletter, though my weekly posts look more like “Harry Styles, the International Space Station, what the hot firefighter show can tell us about modern media, and some LEGO” – so if that sounds like you sign up on my website.

My friend calls this “the Lambton Quay problem” – when you visit a new city and find yourself on the official “main street” (in Wellington, that’s Lambton Quay).

You’re standing there knowing that somewhere nearby is the street with fun bars and great restaurants, but as a non-local, you don’t know where.

This is the whole problem with the current internet: the metaphor of surfing implied motion. The metaphor of platforms implies staying still.

If we agree that community is the heart of the internet – how do we empower people to find one another – to find the vibrant neighbourhood where their kindred spirits are hanging out.

You only get somewhere when you leave the station.

How do we give them a map out of here?

So here’s what I’m asking you to do:

Build something small, weird, and entirely yours

Teach someone else how to build their own corner of the web

Take back control of your feeds and attention

Explore beyond algorithm-curated content

Remember that the good internet still exists – you just need to step outside the walls to find it

The web doesn’t have to be corporate, addictive, or rage-inducing. It can be weird, personal, and genuinely social again. Let’s reclaim it together.

(With thanks, as always, to Su Yin Khoo for the slides)