This is a talk I gave at Beyond Tellerrand in Berlin, Germany and ffconf in Brighton, England in November 2025. Slides and full text below.

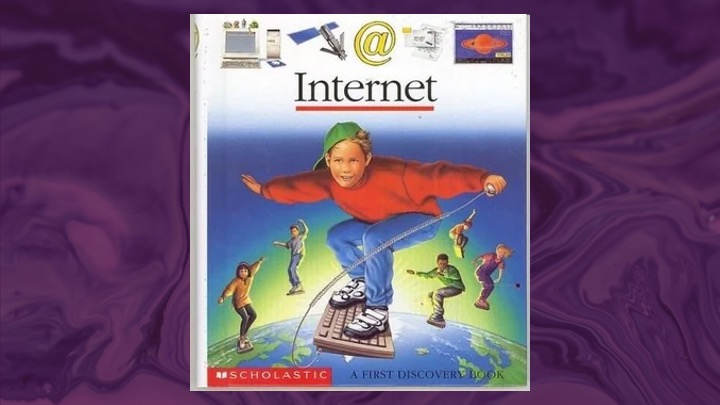

Let’s go back in time, to the birth of the internet.

I know, I know, a lot of you nerds are thinking “amateur – I was dialling up a BBS when you were still in nappies”. But this was how most people encountered the internet for the first time as it started to become mainstream.

Your “front door” to the internet in those early days probably varied:

A university homepage

Yahoo!’s front page

Or, if you were lucky enough to be in Aotearoa at a certain point in time, the Xtra front page

All of these starting points had something in common: a top-down taxonomy. Where do you want to start your journey on the information superhighway? News? Business? Entertainment? A galaxy of possibilities that, well, sounded a lot like sections in a newspaper or areas of the library.

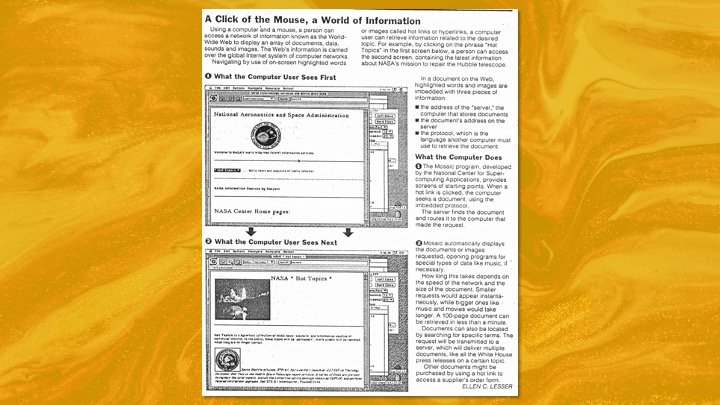

Here’s what the New York Times wrote in 1993:

Click the mouse: there’s a NASA weather movie. A few more clicks, a speech by President Clinton… music recordings compiled by MTV…

… a small digital snapshot reveals whether a coffee pot at Cambridge University is empty or full.

Moving around the early web felt a little chaotic.

When you clicked a link back then, it felt like stepping through a portal someone had built by hand.

Every page looked different, like walking down a street where every house was painted a different colour.

And where many of those people were colour blind.

It’s a quaint vision now. Utopian. Pastoral. Idyllic.

Like reading about some little country town.

When we live here now.

Once online, the novelty of accessing news headlines quickly wore off. What kept people coming back was the ability to connect with others who shared their interests.

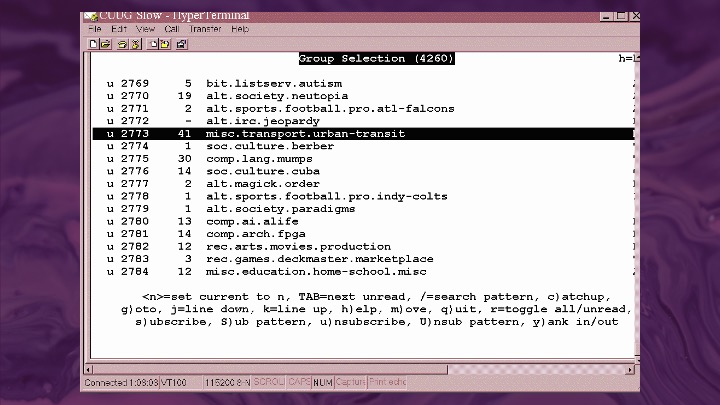

The social heart of that little village was originally Usenet. For the Gen Z in the audience, you can think of Usenet as a kind of proto-Reddit – a bastard lovechild of email and a bulletin board.

In those communities, you could find people from all over the world interested in the same things you were: science, technology, books, TV shows, hobbies.

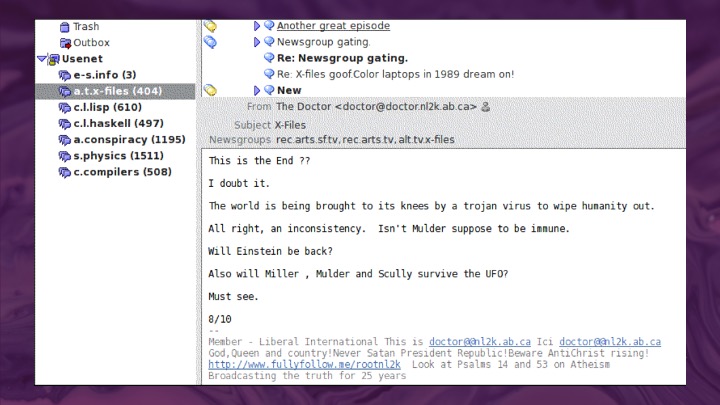

This became my first home on the internet – in The X-Files fandom.

This was my first experience with Transformative Fandom – a community that didn’t just consume media but debated it, reimagined it, and created art and stories expanding its universe.

I dove in headfirst, loving finding people who were as obsessed with the show as I was, speculating on theories, writing their own stories, dissecting episodes that hadn’t even made their way to New Zealand yet.

Looking back, so much of what we take for granted online started in these early communities. This is where online culture was born.

Initially, most online etiquette was dictated by form. We were using computers with very limited bandwidth. Often we were using machines or accounts made available to us through work or college. Posts needed to be concise. Long email signatures were annoying. Posting large files where they would clog up news readers was downright rude.

Before 1993, the internet belonged to the relatively tech-savvy, often university students and researchers.

Every September, when a new cohort of university freshman in the United States got their first email addresses and came online, existing users would have a flood of newbies rushing into their groups and blundering around. It would take a few weeks to adjust, and get everyone on the same page, and then all would go back to normal again.

But Usenet culture changed forever in September 1993, when AOL gave its massive user base access. The influx of new users overwhelmed the community’s ability to teach them the ropes. “Eternal September,” marked a permanent shift in online interaction, because every single day since, there have been more people online.

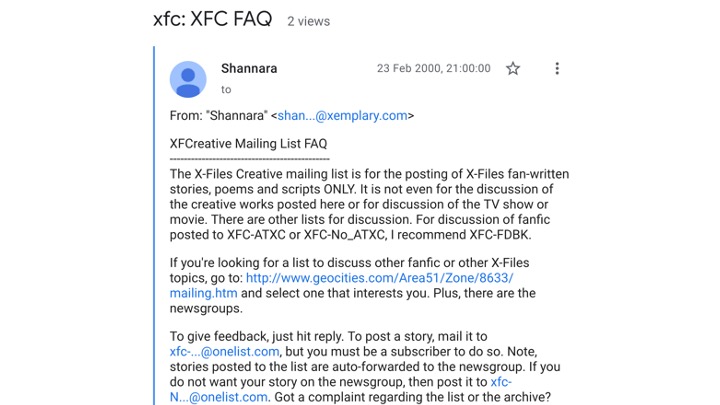

Usenet communities had to find ways to make the experience work for everyone. They would post lists of Frequently Asked Questions – that’s where it comes from – hosted on personal websites, which became cheat sheets for new members trying not to look clueless.

Groups had to start rolling their own governance, coming up with rules for what was in and what was out. And with that came a recognition that if you didn’t want to stay in a particular community or space online you were always free to make your own. Independence characterised this pioneering era.

This phase of the pre-web internet was defined by being:

User-created – we made everything ourselves

Self-governing – communities came up with their own rules, norms, expectations

Community-driven – it was focussed around bringing people together in neighbourhoods

Decentralized – there were no corporate landlords

Was it utopian? No. It was small, homogeneous, and hard to navigate.

In 1994, there were only about 10,000 websites and 2,500 web servers. That’s fewer than there are people that live in each square kilometre of Berlin.

You could buy physical directories – actual books – that mapped the “information superhighway” because it still made sense to have an offline map of the online world.

Search engines were years away from making things findable. We relied on hand-curated directories maintained by individuals.

Jean Armour Polly, the librarian who first coined the phrase “surfing the internet,” liked the metaphor because finding your way wasn’t easy – like the sport it required skill, patience, and a sense of adventure.

I was a baby lawyer in the 1990s, taking my career very seriously. So you can imagine how twitchy it made me when every X-Files story I read started with a lengthy disclaimer begging not to be sued

Turns out it wasn’t just culturally transgressive to read stories where Mulder was doing more than just throwing Alex Krycek against a wall – it was potentially legally transgressive too.

Much of this anxiety stemmed from Anne Rice.

Her books had always been popular but her Interview with the Vampire gained new prominence with the 1994 film adaptation starring Tom Cruise.

Rice was clear about her disapproval of fan fiction. In a 1995 chat, she said: “I’m very possessive of my characters.

I think it would hurt me terribly to read anything with some of my characters. I hope you’ll be inspired to write your own stories.”

By 2000, she was sending cease-and-desist letters to fans – a move later copied by 20th Century Fox for The Simpsons and The X-Files, and by Warner Brothers for sexually-explicit Harry Potter fanfiction.

Fans usually folded, lacking resources to fight legal threats. Today, of course, we’re very familiar with corporations wielding content takedown notices and cease and desist letters, but back in the late nineties, this seemed a lot more confrontational and frightening. The message was clear: transformative fandom was tolerated only as long as it didn’t threaten the bottom line.

This clash represented a new tension between commercial content producers who wanted to leverage the internet to engage fans, but didn’t want those fans doing whatever they wanted online.

Writing in HotWired in 1997, Steve Silberman summarized the “War on Fandom”:

“The problem is that the nature of fandom has changed fundamentally in the past 30 years, while perception of the role of fan culture in marketing campaigns has not. Both the fans and the media companies want to cheat a little.

The media companies want to parade their Web savvy in the marketplace and funnel all Net traffic into a few commercial sites.

The fans want freedom of speech and assembly in sites of their own choosing.”

These clashes shaped fandom’s non-commercial ethos, which persists to this day. Fans learned to operate in the gray areas of copyright law, creating transformative works for love, not profit. But it also put fan communities at odds with the corporations that owned the intellectual property—and, increasingly, the platforms that hosted their work. It certainly didn’t stop us. So, the first thing you need to know about fans is that we will do what we like with your characters.

The second thing? We’re horny.

Actually, this is probably the one thing you already know – because fandom gets reduced to the cliché of weirdos writing explicit stories about Kirk and Spock in the 70s.

But transformative fandom has a long, proud history of exploring relationships between characters never paired on screen.

Valkyrie and Captain Marvel

Draco Malfoy and Harry Potter

Betty and Veronica

And those old men in the Conclave

And what are two things advertisers hate? Infringing IP and explicit content, particularly queer content.

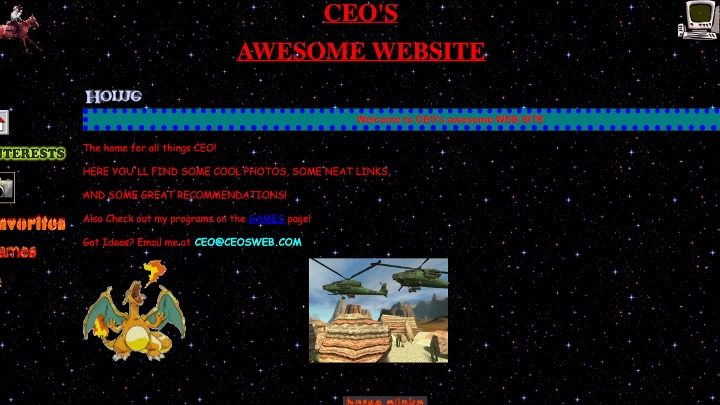

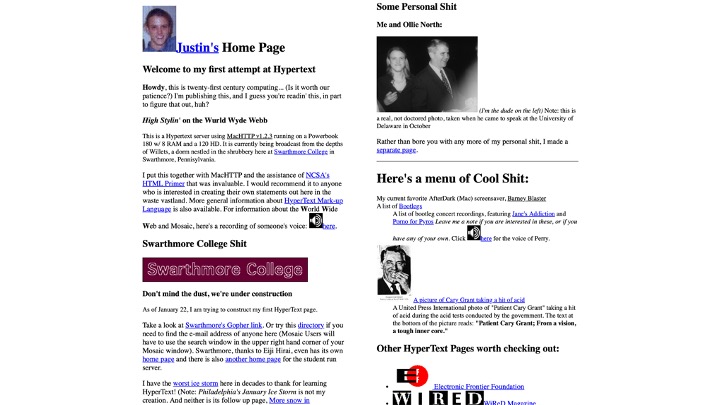

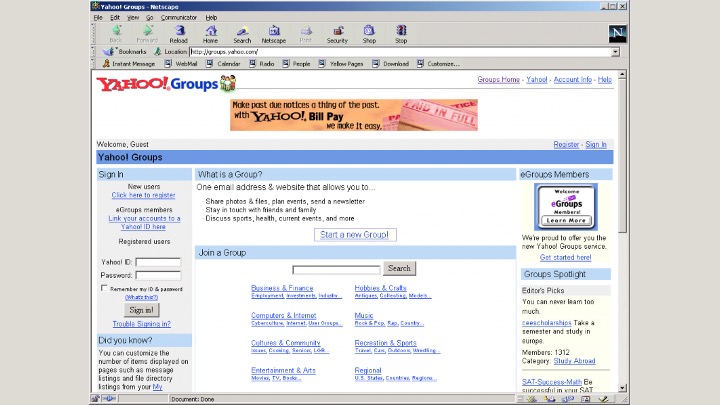

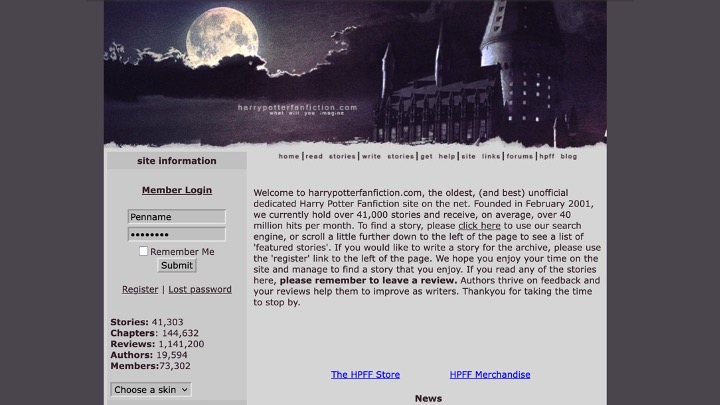

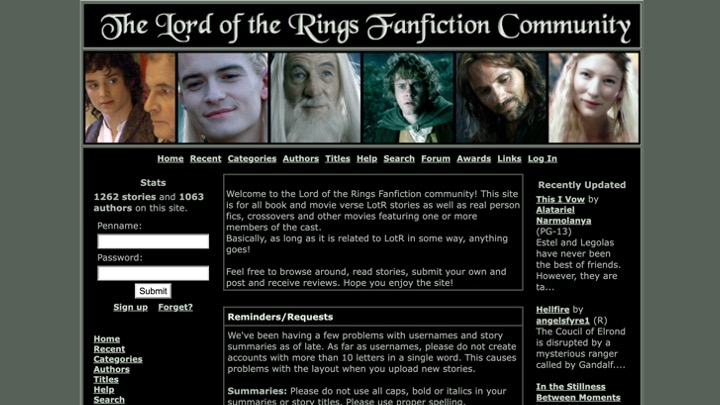

As fans migrated from Usenet to the early web, the communities found a home on Yahoo! mailing lists. And the fans themselves began building their own personal spaces. Geocities pages, webrings, and hand-crafted websites became the norm, because from the outset, fans sought to preserve and protect their creative output.

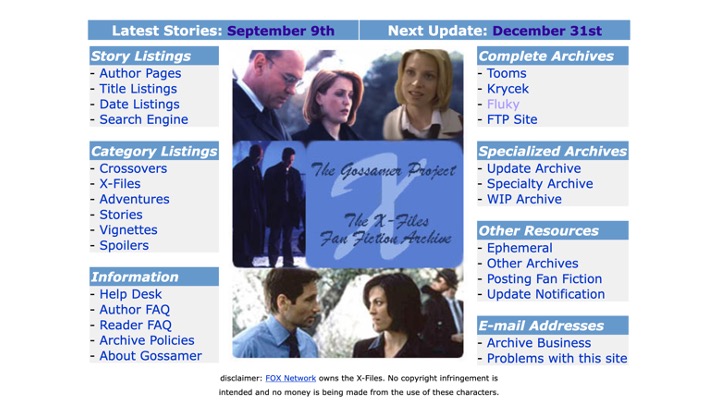

The X-Files was not just my first fandom, but also one of the first fandoms to have a large-scale central archive of all posted fanfiction in The Gossamer Project. Because the archive welcomed all kinds of stories regardless of subject matter, X-Files fans developed a comprehensive way of coding their stories to make it clear to readers what was inside. “MSR” meant the story was about the Mulder/Scully relationship. “UST” stood for unresolved sexual tension between the two. The MPAA rating system was used to denote the content, from G for general audiences to NC-17 for explicit or graphic content. A self-categorising system that would lead the way for content warnings and the tag cloud era to come.

And that was just one fandom. Across the early internet fans were building;

Our own forums – where we could discuss shows and films and books

Our own websites

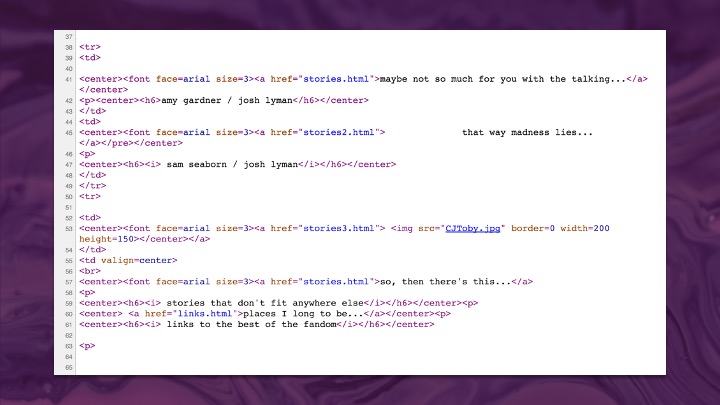

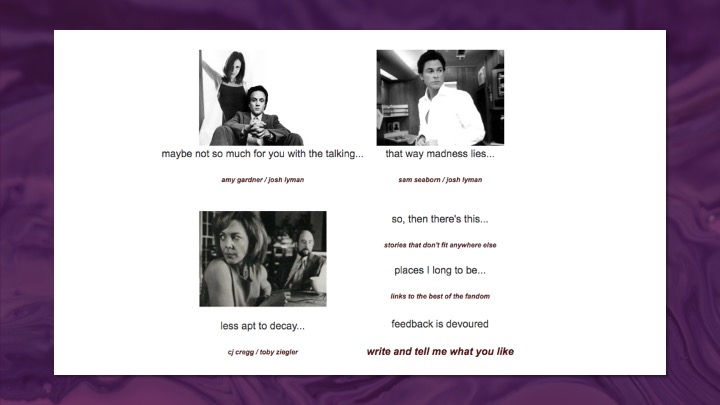

This is mine – the first website I ever built, check out those tables. It was a place to host my West Wing fanfiction.

My fandom friends and I taught each other how to code, design, and maintain our pages. Even as archives became more popular, none of us wanted to lose control of our stories to another site that might not let us change them or take them down, or might disappear overnight. This peer-to-peer knowledge sharing was vital. I learned how to stop hot-linking (because bandwidth was expensive!), how to find episodes in .rar format and recompile them, how to digitise VHS tapes to cut together fanvids, and how to use early music-sharing tools like Limewire to find the perfect soundtrack.

And so gradually I learned to build and maintain my own little corner of the web, and to choose how to share it with others. I linked to my favourite authors. I made rec lists of my favourite stories. I participated in and ran fan-voted awards and exchanges and challenges. I had a whole life, a home, on the DIY web.

These motivations were fundamental in fan communities:

DIY approach

Peer-to-peer learning

Control over our content

Seeking permanence

SO, In the early 2000s, the Usenet/mailing list era evolved into Web 2.0. As fans, we shifted from Yahoo Groups and we landed on LiveJournal and Tumblr – both darlings of web 2.0. While the buzzwords were all about user-generated content, open data, and interoperability

The demon of capitalism was bearing down on us all.

David Karp, Tumblr’s founder, criticised YouTube: “They take your creative works – your film that you poured hours and hours of energy into – and they put ads on top of it.

They make it as gross an experience to watch your film as possible.

I’m sure it will contribute to Google’s bottom line; I’m not sure it will inspire any creators.”

Look where we are now.

Fans have always been early adopters, quick to try new platforms and tools and to make them their own. But they’ve also been quick to abandon them when those platforms no longer served their needs. I’ve spoken here before about my friend Maciej Ceglowski, the founder of Pinboard, gave a talk in 2013 called Fan is a Tool Using Animal, about when Delicious, the bookmarking site that was the darling of the era, made a series of changes that made the site unusable for the fans who had been using it to meticulously tag their fanfiction collections. Seeing the disappointment and unrest among fans on Twitter, Maciej tweeted fans to ask what they might need to make the switch to Pinboard. Over the next couple of days, dozens of fans came together anonymously to collaborate on a Google document, and produced a comprehensive 52 page technical spec.

He says, “having worked at large tech companies, where getting a spec written requires shedding tears of blood…

in a room full of people whose only goal seems to be to thwart you, and waiting weeks for them to finish, I could not believe what I was seeing…

several dozen anonymous people had come together in love and harmony to write a complex, logically coherent document, based on a single tweet.”

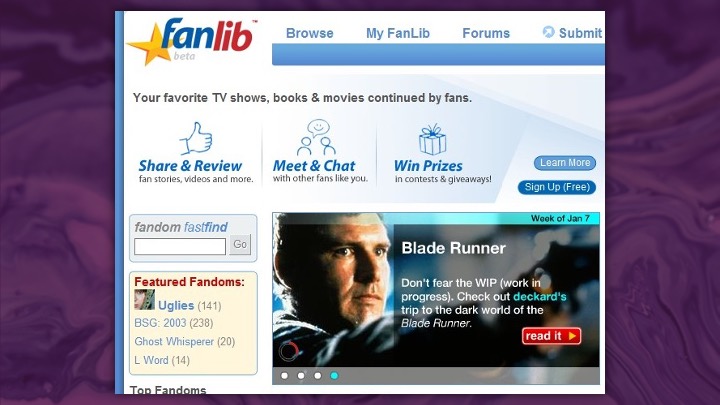

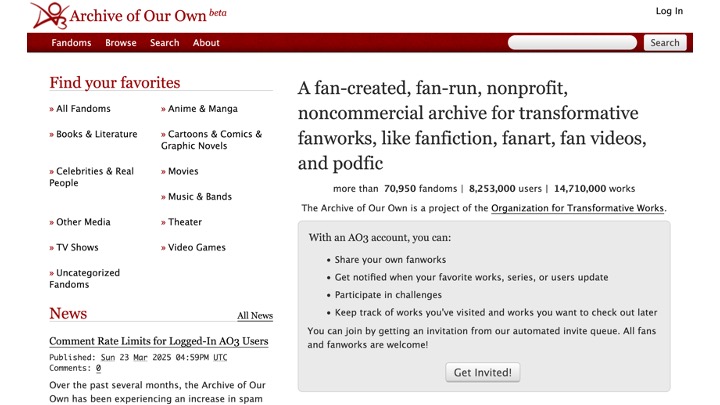

Perhaps the most well-known example of fans taking their destiny into their own hands is the story of the creation of Archive of Our Own. AO3 is a noncommercial and nonprofit central hosting site for transformative fanworks such as fanfiction, fanart, fan videos and podfic. The project started on the heels of a startup company called Fanlib attempting to make a commercial archive that fans would submit their stories to for free. Fans were unimpressed that a company would profit off their creative work, and began to post about alternatives.

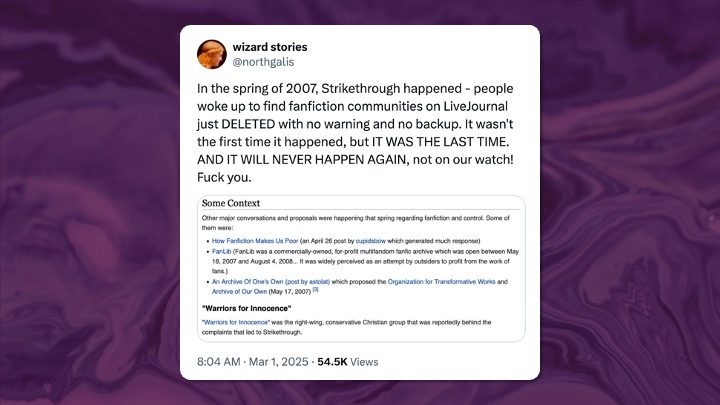

Livejournal (at that stage one of the main online homes for fandom) then bungled an attempt to remove accounts based on a list of “illegal activities” and suspended or deleted hundreds of fandom journals in a moral panic that came to be known as “Strikethrough“. Fans realised that the transgressive nature of transformative fandom was always going to be at odds with companies that wanted to make money off advertising, or were unwilling to defend content on their platforms from complaints and threats.

And which led directly to fans building An Archive of Our Own. The Archive was entirely built and designed by volunteers from fandom. Many of the people working on the project acquired skills in coding, design and documentation through their work on the Archive. When the project went into open beta in November 2009 it had over 20 contributors, all of whom were women, and it remains a shining example of an open source project that has created an inclusive environment that welcomes people without “traditional” development experience. The Archive now has over 16 million uploaded fanworks, 9.3 million registered users, and has fanworks in over 75,000 fandoms.

Fans have always been acutely aware of impermanence – something the rest of the world is just starting to recognize might be a problem, as political winds shift and information we thought would always be available online starts to just vanish overnight.

When Tumblr launched in 2007, fandom took to it like a duck to water. It combined a place to share the strongly visual content that was increasingly possible (photos and gifs from your favourite shows), with a new way of “conversing” through weblogs and tags.

It had the aesthetic appeal of being able to design your own page and theme, which felt like the personal approach of MySpace or Geocities, but far more beautiful. And the dashboard let you curate a personal feed of all kinds of interests in one place.

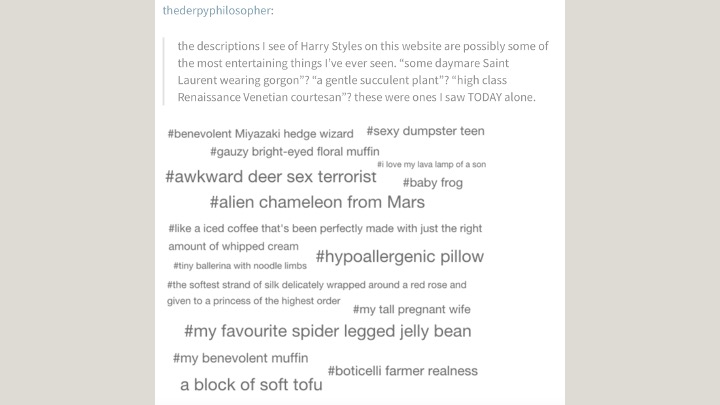

The tag structure made discovery easy, but then was turned into something unique. Fans developed their own tagging systems and also used the tags for conversations and creation in themselves.

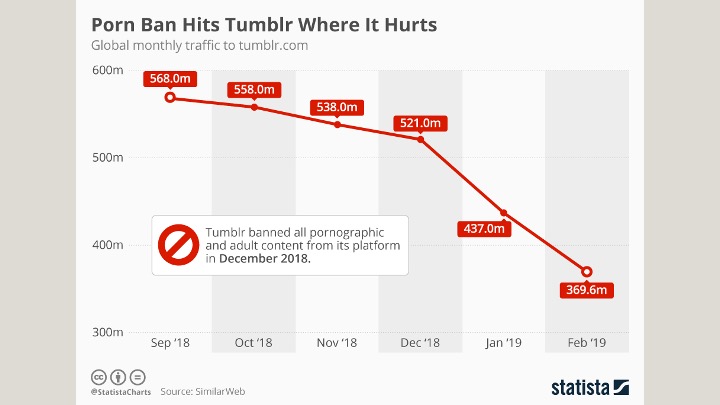

And unlike Facebook, Tumblr allowed for complete anonymity – something that was crucial for fans. Tumblr took on a life of its own, mainstreaming a focus on social justice, sex positivity, and cultural identity for a whole generation long before anyone dared to misuse the word “woke.” But as with Livejournal before it, the time came when the corporate landlords decided to act. In 2018, Apple removed the Tumblr app from the iOS app store because of the ability to access objectionable material on the site.

Instead of acting to improve moderation, trust and safety, Tumblr elected to ban all adult content from the site, sending its user-numbers into a terminal decline. Acquired by Yahoo! for $1 billion in 2013 and sold for $3 million in 2019, fandom diehards are still there sharing gifs of the hot firefighter show, but it’s never been the same.

Fans have long been canaries in the coal mines. Corporate landlords don’t want your infringing IP or explicit content, but they might tolerate Nazis if they pay their bills.

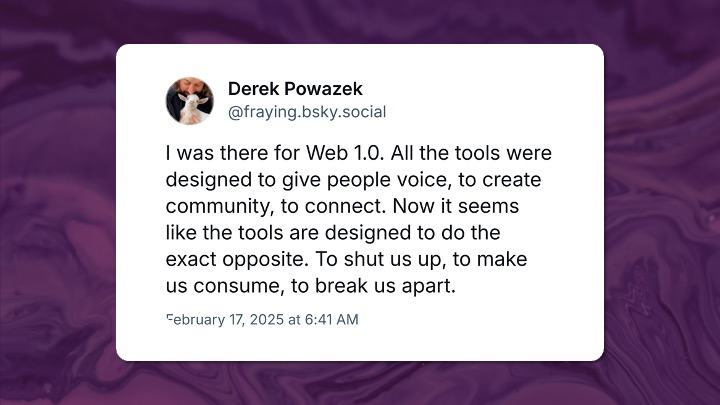

We now exist in walled gardens, monitored by surveillance capitalism, and incentivized to perform engagement through rage.

Nobody wants another “the internet is bad” talk. We all know the utopian vision didn’t materialize.

But, as Molly White recently wrote, the good internet is still there, just outside the walls:

“The walled enclosures that crowded out much of that acre of developed land still reside within an infinite expanse of possibility.

There are no limits to the web – if it has borders, they are ever expanding.

We may feel as though we are trapped in a tiny, crowded, noisy space, but it is only because we don’t see over the walls.”

This inspired me last year to build my second-ever website – a single-serve site to help plan a new layout for my LEGO city.

This is my city. It’s a covid problem that got out of hand don’t talk to me.

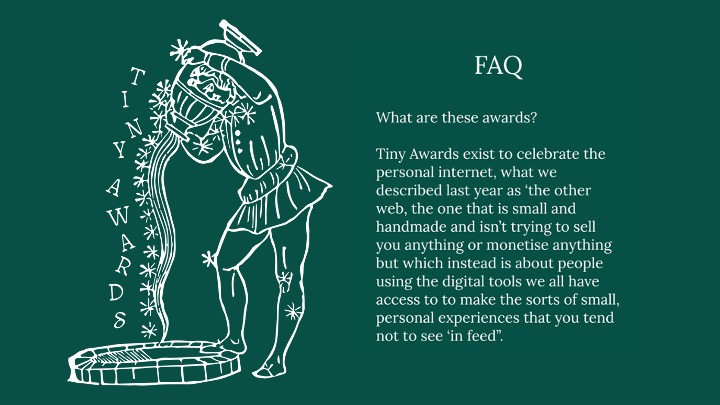

This site became a finalist in the Tiny Awards, which:

“exist to celebrate the personal internet, the other web, the one that is small and handmade and isn’t trying to sell you anything or monetize anything but which instead is about people using the digital tools we all have access to to make the sorts of small, personal experiences that you tend not to see ‘in feed’.”

This is what I want to focus on this year: This other web. The good internet.

Having built only two websites, twenty years apart, gave me insight into how much has changed, for better and worse.

In some ways, we’ve made it easier. Everything is templated. Squarespace lets you throw up a slick site in minutes.

But somehow they all look the same.

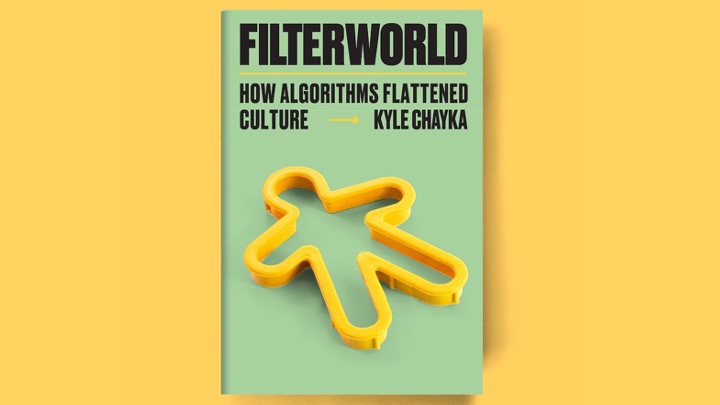

What Kyle Chayka calls “Filterworld” – where algorithms drive all our tastes toward the same flattening end, making coffee shops, Airbnbs, and interior design soulless and drab.

And our corporate landlords are doing it on purpose, chasing the everything app aesthetic.

Take a look at this photo quickly and tell me what app this:

Maybe the border colours in the screenshot tipped you off — but this is how Instagram shows you its app on its own website. Look like the fave photo sharing site you remember?

Let’s go again. Which app is this:

This is Spotify. Try finding the music you love amidst its current front page onslaught of video, podcasts, video podcasts, and audiobooks — I dare you. Then talk to a parent of young kids who has carefully controlled their access to Youtube, only to find that the innocent “music app” is now feeding them the exact same dross.

One more:

This is the one that set me off, actually. This is Substack’s app, jam-packed with every dark pattern I’ve come to hate about the current era.

The independent web never had a single coherent aesthetic, obviously, because everyone made it look like whatever they wanted it to. It was constrained only by what the html/css could do. And so it was individual, chaotic, often weird and it was always personal.

So if web aesthetic = the messy, expressive look of the open internet, and platform aesthetic = the polished, standardised design of closed ecosystems, both aesthetics say a lot about power, creativity, and who controls the experience.Building for the web is easy, and we’ve forgotten how.

And if you know how, when was the last time you showed someone in your life how to make a website?

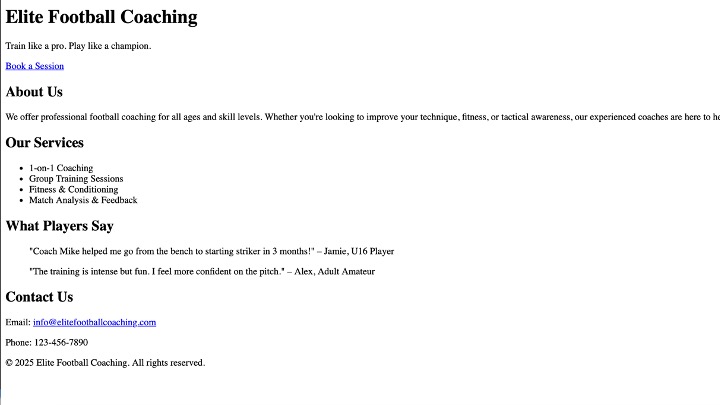

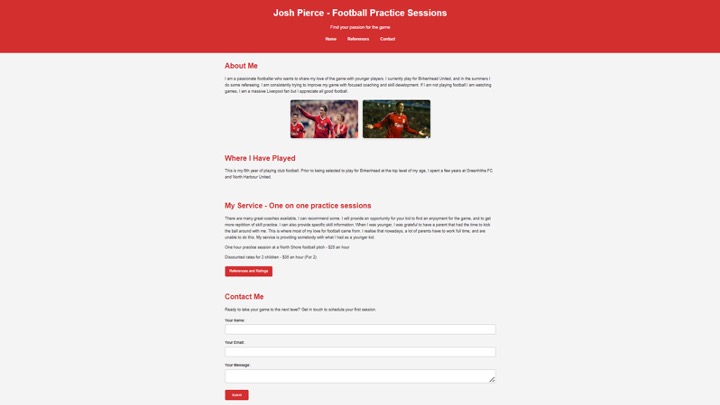

I did it last weekend. My nephew Josh is a really good football player who wants to start coaching kids. So he needs a website and he asked me what service he should sign up for and all I could think was

Why not make it himself?

I knew his eyes would glaze over if I started explaining html from scratch. And so he asked an LLM for the basic code for a football coaching website and I showed him how to save it to his machine. You would not believe how he gaped when he clicked on the index file…

… and how his mind was blown when we added basic CSS. Within 20 minutes he was debugging mistakes the AI was making (and boy does it make mistakes) and changing the code himself.

And within an hour he had a site that started to feel like him.

Here’s what’s easy:

- Writing basic HTML (with AI help available)

- Getting a domain name (relatively inexpensive)

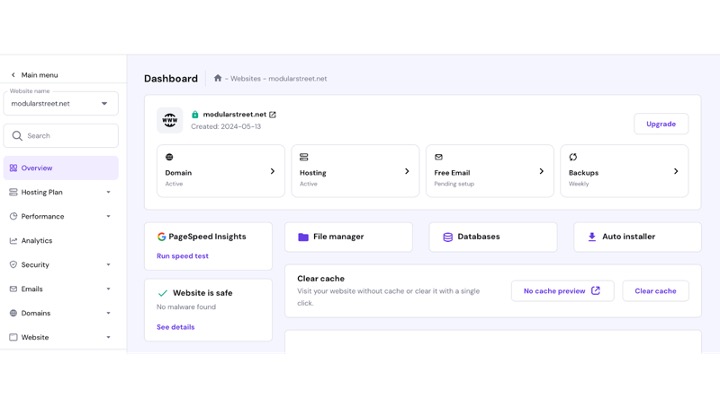

But weirdly hosting remains a challenge. In the olden days, you got free webhosting from your ISP. Now, storage costs are trivial, yet finding an easy-to-use, reliable webhost is difficult.

And when you find one, you’re confronted with FTP clients and technical jargon. I had to dredge my brain to remember how to use this.

The principle here is something I learned from Grey’s Anatomy…

…which is a surgical teaching principle of “see one, do one, teach one.” Fandom has always thrived on peer-to-peer teaching – like fan-binding, teaching others to make physical books of digital fiction and to rebind favourite books series. I learned to do this over the summer from watching fan tutorials on tiktok.

Fans have continued to teach each other technical skills since those early days when I built my first site using only html. Whether its custom css for a tumblr theme, or how to skin your works in AO3 or how to edit a podfic, you can find resources from other fans for free teaching you how to do all this online, and groups where you’ll find people willing and eager to help. What if we applied see one, do one, teach one to building for the web again.

We’ve stopped exercising our digital agency. Manual processes feel too hard (sorry, Fediverse fans).

Here’s what we need to change:

WHERE we consume

HOW we consume

WHAT we consume

Let’s start with how…It’s long past time to turn your back on “recommended,” “for you,” and “you might like” – and to control your scroll.

Until recently, this was nearly impossible with social media. Being on Twitter, TikTok, or Instagram meant being at the mercy of whatever black-box algorithm drove the most engagement – a firehose to the face. These platforms quickly learned that hatred, conflict, and fear drive engagement.

Like many, I joined Bluesky when Twitter was acquired. I thought it was nostalgic but not revolutionary. I told people, “Whatever comes next won’t be a Twitter clone.” Now I’m not so sure.

You might have seen Bluesky CEO Jay Graber at Sx recently wearing her “World without Caesars” shirt, to contrast with Meta CEO’s Zuck or Nothing. Bluesky doesn’t want emperors or to control your feed.

Old Twitter let you create “lists” to check in on specific accounts. But Bluesky lets you make entire feeds, customizing your whole social media experience. Mute words, block accounts, filter out Amazon links, hide NSFW content, or highlight mentions of your favorite blorbo – all possible with custom feeds.

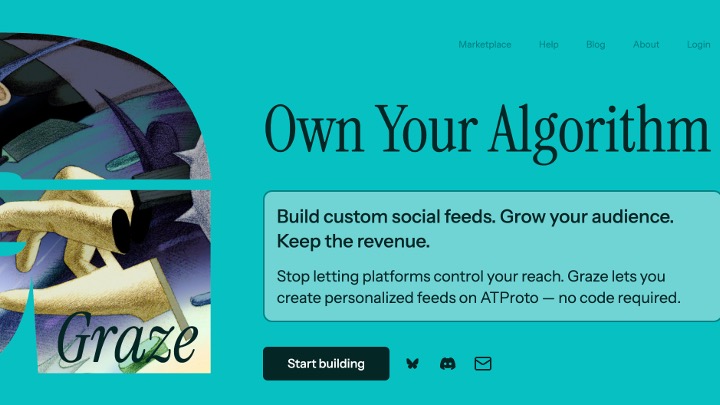

I’ve been spending time with the team building Graze – a low/no-code feed builder for Bluesky that’s changed my whole experience. Make feeds public or private, opt in or out, use them for community building.

Similarly, Rudy Fraser and BlackSky continue doing amazing work with feeds by and for Black users.

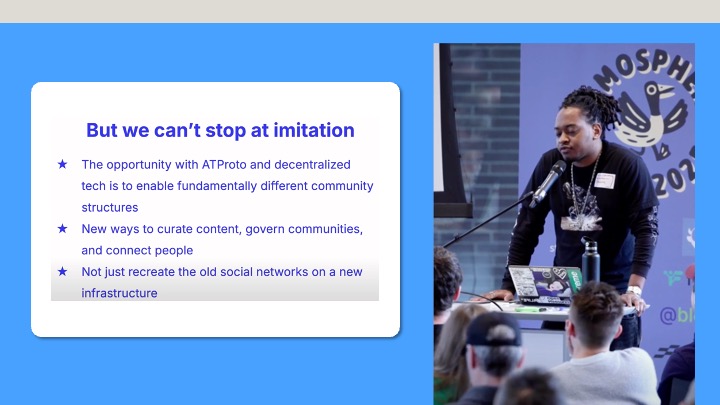

Speaking at a conference recently Rudy described Bluesky as a skeuomorphism. It looks and feels like twitter but we need to move beyond that shorthand to take advantage of everything the new infrastructure offers us.

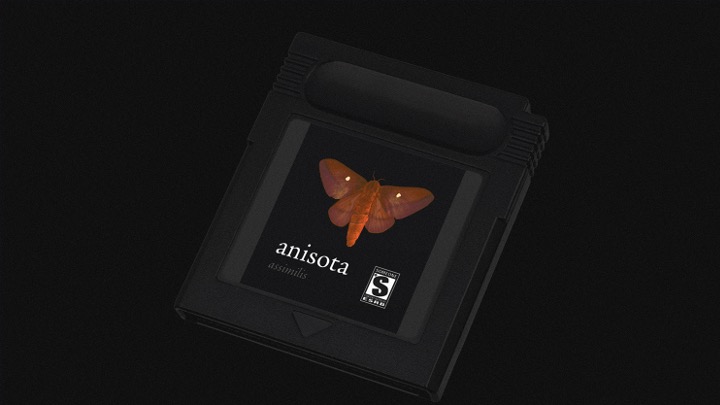

Anisota is an avant garde client for bluesky. You don’t “scroll” through an endless feed of posts. Instead, you flip through a finite deck of cards until you run out of stamina. You don’t see engagement metrics front and center, instead each post has a “rarity” icon as if it were a trading card. You can collect post cards into curated decks that can then be shared with others. There are even in-game items, specimen collecting, and soon to be quests.

The creator dame says: I wanted a way to continue using social media without having to subject myself to many of the dynamics that are not as healthy or compatible with my lifestyle/values/demeanor. I love technology, but after a decade of experiencing the best and the worst that it has to offer, I realized that the status quo of the internet and social media was not sustainable, grounding, or conducive to human flourishing. I don’t know if Bluesky’s growth will last, but the ability to curate your own social media is something I’ve wanted for years

I’m also interested in apps like Tapestry, which bring all your various feeds into a central place. I’m not sure I want to scroll my hockey tumblr thirst posts alongside US political doom, but I am interested in what’s next.

How we live online needs to change.

In particular, I want us to think hard about what’s next for groups.

This is my local community last weekend getting together to build sandcastles and protest a proposal to mine sand from our bay.

Whenever I see small communities trying to form, whether it’s fan subcultures, neighbourhood initiatives, volunteer teams, parents wrangling kids’ sports, they hit the same wall: there’s no good online infrastructure for intentional groups. We make do with whatever’s available: WhatsApp chats, private Slacks, Discord servers, Facebook Groups, Substack comments. They all kind of work, but not for long. Because these are not tools for communities. They’re tools for communication, and that’s not the same thing.

And none of these groups are discoverable easily. Where do you go when you’ve just taken up embroidery and want to talk to people outside of crafters’ tiktok comments? How do you find fans who care as much about a new Netflix show as you do (watch Boots, I beg)? You now have the email addresses of all the people at the dogpark, but noone wants to copied on an email in the clear?

Worse, possibly, we’re all on the verge of message bankruptcy at all times. We don’t want more unread notifications, and we don’t want more places that we have to check in order to stay up to date.

I talk all the time about wanting us to build healthy, vibrant online neighbourhoods. “Bars” we want to hang out in (or farmers markets, or parks, or whatever your metaphor is). But to do this we’re going to need some new tools.

Here’s what I think a new neighbourhood tool would need, but you might disagree or have better ideas:

Persistent archives. Newcomers can learn history, you’re not always asking for the building’s security company’s details, or the recommendations for local hairdressers, or the hours of the school pool over the summer.

Transparent governance tools. Some shared decision-making, moderator accountability, no ability for the owner of the group to flounce dramatically and leave everyone stranded.

Layered privacy. Granular sharing options, so you can choose who sees what.

Federation & portability. No, not the neckbeard kind. But communities should be able to move or connect to one another.

Healthy digital spaces need the same foundations as physical ones (roads, rules, records, etc) so we can build the flourishing fun bits on top. If the web’s first generation gave us villages, and the second gave us gross, unliveable megacities, the next one should give us great neighbourhoods — small, knowable, human-scaled spaces where we can actually live together online.

The thing about neighbourhoods is that they don’t appear by accident. Someone has to plant the trees, pave the footpaths, decide where the park benches go. The same is true online. We need infrastructure that makes it easy for groups to stay — not just start. Right now, we’re trying to host potlucks in chat apps built for drive-through service. Let’s work out how to change that.

Next up is WHAT we consume.

Clive Thompson wrote a great piece on “Rewilding your Attention” – thinking about how we can go strolling to look for weird things online.

I want everyone here to take up the banner of reweirding the web.

Fans love weird – we’ve invented a whole fandom around a fake mob movie from the 70s that came about because someone posted a picture of their shoe. It referenced a Scorcese film called Goncharov that didn’t exist. Someone on tumblr tagged it “this idiot hasn’t seen Goncharov” and away we went.

People posting essays about the themes of the film, the characters, how certain scenes should be interpreted, creating the posters, making the soundtrack.

There are over 700 Goncharov fanfics on AO3. Scorcese’s daughter texted him to ask if he’d seen it.

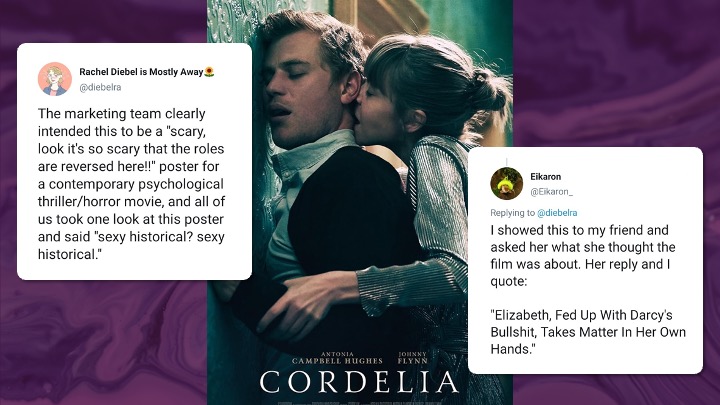

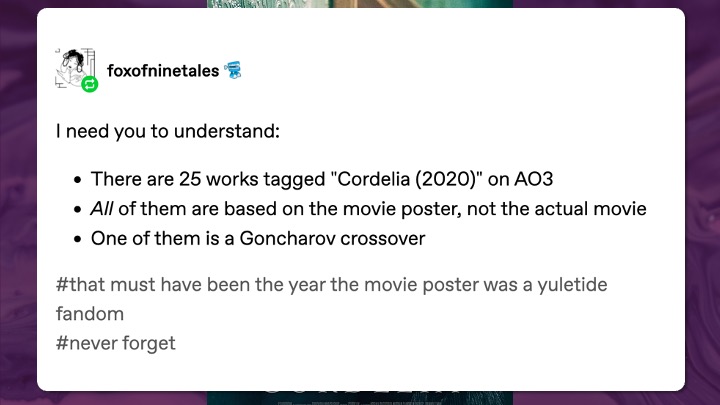

We’ve misread posters and turned THAT into fandoms. When the poster for this film Cordelia dropped, everyone on tumblr somehow saw this as a period film. You have to stare at it to realise it’s not – they’re wearing contemporary clothes.

Anyway – one of them is a Goncharov crossover.

My point is we need to take that weirdness everywhere.

Here’s a bunch of things I’ve seen just in the last month or so:

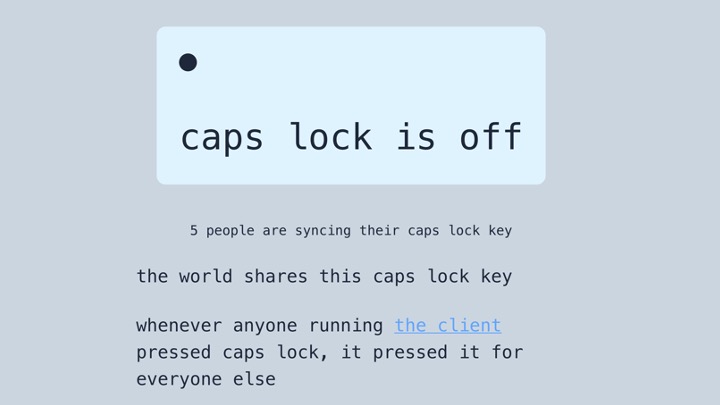

Global capslock was a project where you ran a little client in the background and, when one person pressed capslock it came on for everyone else:

This site shows you where the closest panda is and what its name is.

Here are your closest pandas!

My friend Erika started painting chickens to deal with the state of things in America. Then she decided to try and reset the timeline to before the internet took the particular turn that created Facebook. What if we did the same simple interaction, but *not* in order to compare the hotness of nonconsenting teens? Clickens was born.

Traffic cam photo booth. Find your nearest traffic cam, go and pose for a pic.

And then this one is hard to describe:

I tried it out, 30 seconds to record is harder than you think!

Imagine if everyone in this room made something fun, weird, pointless, useful. Something that solved a problem only you had. Or didn’t solve anything at all but made you smile. Or made your nephew smile.

Finally, WHERE we consume – We need to think differently about our digital neighbourhoods.

Everything old is new again – like the return of Digg.

But we also need genuinely new things. We didn’t know we needed Twitter when we built it. Remember when everyone mocked it as the app where you posted your sandwich – not dismantled democracy?

We need to stop thinking about audience; and start thinking about discovery in an era when AI-generated content has destroyed search.

I too have a newsletter, though my weekly posts look more like “Harry Styles, the International Space Station, what the hot firefighter show can tell us about modern media, and some LEGO” – so if that sounds like you sign up on my website. We’re relying on human curators again because it’s hard to find our way around.

My friend calls this “the Lambton Quay problem” – when you visit a new city and find yourself on the official “main street” (in Wellington, that’s Lambton Quay).

You’re standing there knowing that somewhere nearby is the street with fun bars and great restaurants, but as a non-local, you don’t know where.

This is the whole problem with the current internet: the metaphor of surfing implied motion. The metaphor of platforms implies staying still.

If we agree that community is the heart of the internet – how do we empower people to find one another – to find the vibrant neighbourhood where their kindred spirits are hanging out.

How do we give them a map out of here?

As we start to focus on building the good internet, it’s cute and fun to nod to the retro stylings of the web1.0 era — reinventing webrings and blogrolls and giving everything an anti-squarespace feel. But whatever is next shouldn’t be retro. It should be its own thing.

I think the new web aesthetic is about getting active again. Platforms encourage passivity. They want us to stay still and scrolling, looking at what the algo wants to show us. Like, swipe, repeat. But the new web aesthetic is non-linear. It encourages you to move from one site to another, to dive down rabbit holes, and crucially, to continue sharing what you find.

The new web aesthetic is link-heavy. It constantly references out to other spaces, to past work and to related ideas. It sees the web as an ongoing conversation, not a feed. You’re encouraged to leave the page.

Sites that reflect a person’s process, not just their conclusions. It’s working with the garage door up.

Makers like my bestie Adam share their process generously on social media – complete with the prototypes and the mistakes and the things they’d change for next time. I want us to do that with our THINKING and our EXPLORING.

I don’t just want to see the polished end result that’s ready for sharing.

And with that in mind I made something for all of you. Scan this qr code and you’ll be able to download a field guide to one of my recent rabbit holes. It’s just an example of an attempt I made to map one of these journeys, as I think about how we can share this work in progress more actively.

I want us all off the platform, because you only get somewhere when you LEAVE THE STATION.

So here’s what I’m asking you to do:

Build something small, weird, and entirely yours

Teach someone else how to build their own corner of the web

Take back control of your feeds and attention

Explore beyond algorithm-curated content

Remember that the good internet still exists – you just need to step outside the walls to find it

The web doesn’t have to be corporate, addictive, or rage-inducing. It can be weird, personal, and genuinely social again. Let’s reclaim it together.

(With thanks, as always, to Su Yin Khoo for the slides)